UW astronomers ride a wave of discovery

Apache Point has been a mainstay of the UW astronomy program, but faculty have also had a hand in many other major national projects in astrophysics. They have participated on teams to develop instruments for the Hubble Space Telescope and similar telescopes in orbit. They led NASA’s Stardust, the first U.S. mission to collect dust from a passing comet. They have advised on the development of powerful supercomputers used by theoretical astrophysicists. They helped found the UW Astrobiology Program, which studies the Earth’s past environments and looks for possibilities of life within our solar system and beyond. And they have been leaders in survey astronomy, which uses specialized equipment to map the sky.

Try Adsterra Earnings, it’s 100% Authentic to make money more and more.

The UW got into survey astronomy early as a participant of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), completed in 2000. While other telescopes aim to capture faint light from the earliest galaxies, wide-angle telescopes like the SDSS’s study the sky to map cosmic patterns and identify changes over time. Data collected by SDSS is open source, available to anyone with a computer—including UW undergraduates, who have identified a thousand new asteroids.

Scott Anderson, chair of the astronomy department, insists it’s not hyperbole to describe SDSS as among the most successful projects in the history of the field. “That’s true by all kinds of independent measures,” he says, “including how many Ph.D.s it has produced, how many publications it has produced, how many people are engaged in citizen science.” Many SDSS discoveries—from the chemical composition of thousands of stars to patterns in the distribution of galaxies—provide clues to the history and fate of the universe.

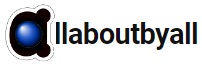

Given the success of SDSS, it’s no surprise that the next generation of survey telescope is in the works—and that UW astronomers are involved in all aspects of planning and design. The Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) will be an 8-meter instrument featuring a digital camera about the size of a Volkswagen Beetle. The camera, based in Chile, will take three pictures every minute, completing a survey of the visible sky every three nights and producing an almost unimaginable trove of data. As with most major astronomy initiatives, much of the funding comes from the National Science Foundation.

“The LSST is one of the most exciting experiments in astrophysics today,” says Andrew Connolly, professor of astronomy. “When it comes online at the end of this decade, it could completely transform our knowledge of our universe, from understanding how dark energy drives the expansion of the universe to identifying asteroids that may one day impact the Earth.”

No doubt any new discoveries will lead to many more questions—which is, after all, the fun of research.

“Fifty years ago, I would have thought, ‘We’re going to understand all of this someday,’” says Balick. “However, the more we find out, the more new questions emerge, which is humbling. The future will certainly bring us many wonderful surprises no matter how it plays out.”

More Story on Source:

*here*

UW astronomers ride a wave of discovery

Published By